Whisky Production Process

Published August 1, 2020

Contents

While every distillery has its own recipe for making malt whisky, they all largely follow a basic recipe. The process, although strictly regulated, offers a lot of leeway for the master distiller to create his own style. Each step affects the character of the malt. Let’s find out how Uisge Beatha is made and how the flavors get into the whisky.

Ingredients

whisky consists of surprisingly few basic ingredients; grain, water and yeast.

Barley

Malt whisky is made using malted barley, different barley varietals are used and these tend to change peridoically as better yielding forms are found. The selection of barley, unlike, for example, grapes for wine, is seldom taste-oriented. Instead, more technical criteria are followed, such as grain size, nitrogen and moisture content.

There are three main arguments for this,

- The contribution of barley to the taste of the whisky is itself comparatively small

- The differences in taste between different types of barley are negligible

- The distillation and maturation process eliminates most of the characteristics

Water

Water is very important in whisky production, the hardness, the amount of dissolved minerals and the peat content of the water all have an influence on the yeasts ability to create alcohol, and the final taste.

Yeast

Yeasts are living organisms that convert sugar into alcohol. The Scottish whisky industry likewise has historically taken a largely pragmatic attitude towards yeast. The contribution of yeast to the taste of the end product is considered negligible and the only important aspect is efficiency when producing alcohol.

As a consequence, the Scottish whisky industry has largely used the same yeast strain. In Japan, the second large single malt producing country, and America the third, distillers are more experimental with yeast strains. In recent years however a number of distilleries in Scotland and Ireland, particularly the newer (built from around 2010 onwards) ‘progressive distilleries’ are experimenting with yeasts in search of new flavor profiles. This is largely in an effort to try to find a competative edge and hasn’t really trickled to the dominant players as of yet.

Production

Malting

Barley consists primarily of starch, and is undigestable to yeast. The process of malting manipulates moisture levels to trick the grain into believing that it is time to grow. To achieve this effect, the barley grains are first bathed in water and then left to germinate in a cool, moist environment being turned regularly. During this process, enzymes are activated that later convert the starch of the barley into sugar. The difficulty is in stopping germination at the right moment. To do this, the germinating barley has to be dried again.

Drying

To dry the malt and halt the germination process, the malted barley is kilned over a heat source. There are different ways of drying.

- Hot air drying, using electricity, wood or coal fires - the heat stops germination, kills bacteria and other pests. This type of drying has little effect on the taste.

- Kiln over the peat fire: If the distillery decides to kiln the malted barley over the peat fire, the malt is not only dried, but also takes on the smoky taste typical of Islay and many Highland distilleries. The phenols in peat smoke combine with the surface of the barley grains and later give the whisky the special, smoky taste for which Scotch whisky is so famous.

The more peat smoke the barley is exposed to, the stronger the later smoke aroma. Most mainland malts are only relatively lightly peated, while whiskies from the islands, especially Islay, are known for their heavy peat and the resulting smoky taste.

Griding

In the next step, the finished malt is then crushed into a combination of around 70/20/10 ratio of ‘grist’. This is generally 20% husk (coarse) 70% grits/heart/middles (medium) and 10% flour (fine). This is typically done at the distillery usually on ancient Porteus and Boby malt mills.

Mashing

The malt grist is mixed with several batches of hot water in a mash tun, the exact number varies though 3 runs of how water are the average. As soon as the meal comes into contact with the water, the enzymes set in and the further processing of starch into sugar (especially maltose) begins. The result is a very sugary liquid, which is also known as wort.

The wort is separated and collected through the perforated bottom of the mash tun. The process is repeated with increasing water temperature in order to extract as much sugar as possible. The remaining spent grain, commonly called draff is then either sold to farmers as feed for livestock, or used for the creation of biofuels.

In the next step, the wort is pumped from the mash tun into the fermentation tank (washback). The speed with which this process is carried out has an impact on the later taste of the whisky.

- Slowly: The master distiller slowly pumps the wort out of the mash tun. It receives a clear wort, which creates a spirit without a strong grain character.

- Fast: If the producer decides to pump out the wort quickly, he receives a cloudy wort, which still carries some solid components from the mash tun. As a result, the spirit takes on a dry, grain-like, nutty character.

Fermentation

After the wort has cooled down, usually via a heat exchanger, though traditionally via means of a Mortons refridgerator it is pumped into the fermentation tanks (washback), yeast is added and fermentation can begin. During fermentation, the yeast converts the sugar in the wort into alcohol.

The master distiller can then further influence the character of the final whisky by altering the length of the fermentation process.

- Short fermentation (~ 48h): If the master distiller opts for a short fermentation, the brandy will show a more pronounced malt character.

- Long fermentation (> 55h): If the distiller chooses the long fermentation route, so-called esters are created in the wash, which are reflected in lighter, complex and fruity aromas.

The fermentation process is very virtually identical to that for brewing malt vinegar or beer. The loquid created after fermentation, called wash, is a beer-like alcohol of around 8% ABV.

Washbacks are either traditionally made of wood or of stainless steel. The material of the fermentation tanks may contribute to the final appearance of the whisky, though this is hottly debated by distillers. Those in favour of Douglas Fir argue that the wooden washbacks develop their own microclimate over the years, despite regular cleaning. The main difference in practical terms is the need for cooling, alcohol production produces lots of CO2 and huge amounts of heat. In wooden washbacks the heat never rises to a level that could threaten the yeast, stainless steel washbacks being great heat carries must be cooled to avoid killing the yeast prematurely.

Distillation

The process varies slightly between grain distilleries which leverage a form of continuous form of distillation and so called pot still or batch distillers. The process described below concerns pot distillation using two stills, though tripple distilation was once the rule of the Scottish Lowland region and is still common in Ireland.

In the next step, the mash is pumped into the first, copper still (called a wash still) and a raw spirit, the so-called ‘low wines’ at around 23% ABV, is produced. The distillation process is then carried out a second time in a second copper “spirit still”. This second distillation separates alcohol, smells and flavors from the water and concentrates them.

The Influence Of Copper On Whisky

A big factor in the final taste that comes into play during distillation is the copper in the stills. Although no copper remains in the finished whisky, the copper walls of the still act as a catalyst and help filter sulphurous compounds from the finished whisky. The master distiller can exert some influence on the length of the contact time between alcohol vapors and copper:

- Long copper contact: Long contact between the copper and alcohol vapor ensures a lighter, milder spirit. Accordingly, particularly high stills produce a lighter spirit. An example is a distillery from the Highlands. The Glenmorangie distillery has the tallest stills in Scotland (5.4m) and is world famous for its light whisky.

- Short contact with the copper: A short contact between the copper and alcohol vapor ensures a heavier whisky. The effect can be created by rapid distillation or particularly small stills.

Methods to manipulate the amount of reflux produced, where spirit recondenses on the side of the still, or in the line arm before falling back into the still to be distilled again have been tried at several distilleries. The most famous example of this being the Lomond still variations of which are still in use at Loch Lomond, and were the basis for the Glencraig and Mosstowie whiskies.

Condensation

After distillation, the alcohol vapor must be returned to its liquid state. To do this, the steam is fed into a condensation systems. The type of condensor used has an impact on the final taste:

- Shell and Tube: A shell and tube condensor, sometimes called a recuperator consists of a hollow cylinder filled with cold water, which contains a large number of copper tubes. When the alcohol vapor touches the cold pipes, it cools down and becomes liquid. Due to the relatively high ratio of steam to copper surface, whiskies produced with shell and tube have a lighter character.

- Worm Tubs: Traditionally, so-called worm tubs are used in Scottish distilleries for recondensation. The alcohol vapor is cooled in a long copper pipe, which is located in a water tank. The contact with the copper is rather short, so the whisky becomes comparatively heavier.

Worm Tub condensors are generally credited for the heavier, meatier flavours of whiskies such as Mortlach.

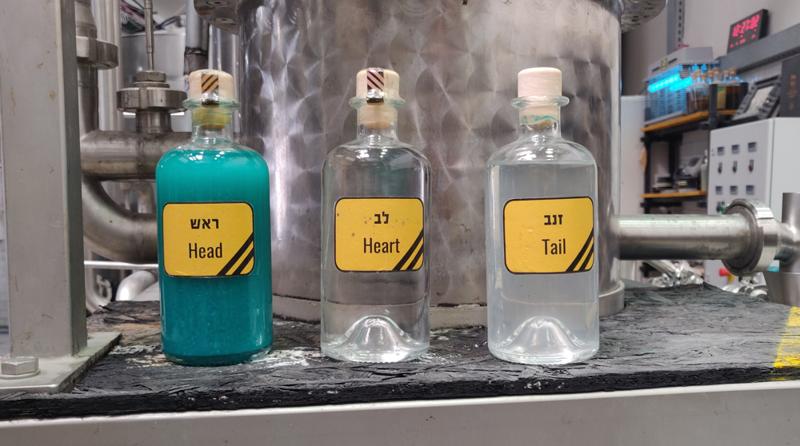

Foreshots, Middle Cuts and Feints

The fine spirit produced in this way is generally separated within a spirit safe by the master distiller into three parts, the middle cut or “heart”, the foreshots or “head” and the tail (feints or “tail”).

The middle run runs over a counter, which determines the spirits tax to be paid. The foreshots and feints are not used in the next step, but are instead recycled and added back to the next batch of raw spirit for further distillation. The middle cut constitutes the newmake spirit which will be put into oak barrels for maturation.

The times at which the master distiller sets the cuts for the separation of pre-run, middle run and post-run also influence the taste of the whisky. During the ongoing distillation process, the aromas change in the spirit - while light, filigree aromas predominate at first, oily, rich aromas are added later. If the master distiller wants to produce a light whisky, they will set the cut early. Conversely if the whisky is to be heavy and rich, then the cut will be made later.

Cask Maturation

The Newmake is usually then diluted with water to achieve an alcohol strength ~ 63.5% ABV before being put into cask. The reduction varies and some distilleries cask at a higher ABV but 63.5% is the standard and generally deemed ideal for both transportation and safety. Subtractive, additive and interactive maturation take place during the 3+ years of maturation.

Subtractive Maturation

Subtractive maturation ensures that the aggressive, metallic character of the Newmake is removed from the finished whisky and ensures that any unpleasant sulpherous notes are reduced.

Additive Maturation

Additive maturation describes the enrichment of the whisky with aromas and flavours from the cask. The exact influence will vary based on the type of oak used, as well as the previous fill.

Interactive Maturation

Interactive maturation describes the exchange of aromas and flavours between wood and whisky, which gives the finished malt its complexity. The exact combination of flavours created will vary based on a number of factors.

The duration of maturation, size and previous contents of the barrel (typically bourbon, sherry or other fortified wine), freshness of the barrel (1st fill or refill) and possible finishes in other barrel types have an enormous influence on the taste.

Blending and Bottling

Unless the whisky is destined to be sold as a single cask during the final step, the master blender selects multiple barrels for filling from the barrels of the distillery. In the case of Scotch whisky, the barrels were matured for at least 3 years beforehand, but generally far longer.

Single Malts

Contrary to popular belief, a single malt usually consists of whisky from different barrels. These are generally all around the same age and being blended to create a signature style such as the Bunnahabhain 10, Laphroaig 18 etc. though different ages may be used if the whisky is being sold as a No Age Statement (NAS).

Blends and Blended Malts

If a single malt is not being produced, that being the named product of a single distillery, then the cask will be mixed with a combination of casks from other distilleries. If these are also single malts the whisky will be called a blended malt (traditionally Vatted malt), if grain whisky is used the resultant mix will be called a blend.

Chill Filtration

After the selection of the casks, one of two controvertial decisions will then be taken. Whether the whisky is to be subjected to chill filtration, a process that removes esters and fats from the whisky ensures it does not become cloudy at lower ABV and low temperature. If whiskies are sold at 46% ABV or higher it can generally be taken for granted that chill filtration has not taken place.

E150A (Spirit Caramel)

The second controvertial decision is whether or not spirit caramel is added to the whisky to unify the color. This decision is also in essence a question of marketing.

As whisky is a complex natural product, every cask and every vintage is slightly different. Master blenders are looking to recreate a flavour rather than a colour and so small colour variations may exist between bottlings. Spirit caramel is used in this capacity to normalise the whiskies colour.

Previous

Next