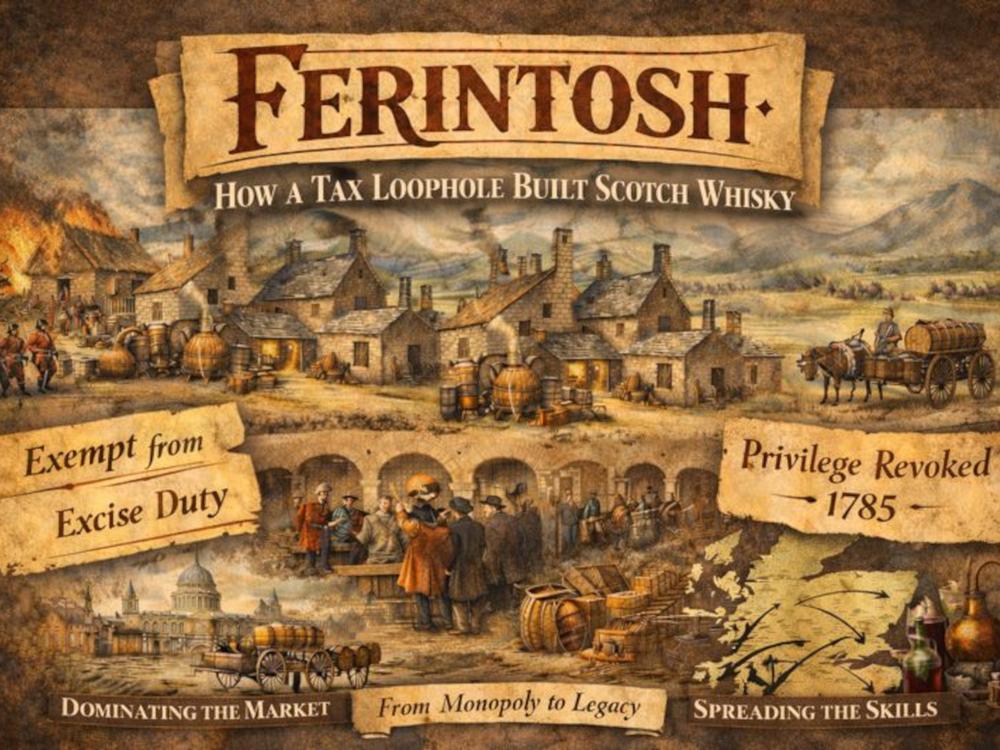

Ferintosh: How a Tax Loophole Built Scotch Whisky

Published November 26, 2025 by John Fegan

Ferintosh was not an ancient distillery but a late-seventeenth-century Highland estate operation that became disproportionately influential because it alone was granted perpetual exemption from excise duty on distilled spirits. This privilege, awarded in 1690 as compensation for Jacobite destruction of the Forbes family estates, allowed Ferintosh to produce whisky legally and cheaply on an industrial scale. By the 1780s it accounted for over a third of all legal Scotch, supplied London rectifiers, and undercut every taxed distiller in Scotland.

Persistent lobbying led to the withdrawal of the privilege in 1785, after which Ferintosh production collapsed. Its trained workforce dispersed to Campbeltown, the Lowlands, and beyond, spreading technical expertise and accelerating the growth of the wider Scotch whisky industry. Ferintosh did not disappear; it became the template.

Described in the Scottish Parliament in July 1690 as an “ancient brewery of aquavity”, the Ferintosh estate distillery was nothing of the sort, unless ancient is taken to mean “older than the speaker’s own memory but younger than his father’s decisions,” which in the 1690s, given the average lifespan, was practically yesterday and entirely respectable if your family owned land.

In reality, Ferintosh had not been operating since time immemorial, but for less than thirty years. This was still considered venerable, because most people did not live long enough to argue the point, and those who did were rarely invited to Parliament.

After Duncan ‘Grey’ Forbes of Aberdeenshire bought the barony of Ferintosh in 1625, and later the Bunchrew Estate in 1670, he set up a small still in the 1670s. This was not destiny so much as arithmetic. Grain was surplus, water was abundant, and sobriety had yet to prove itself useful.

While Forbes was in Holland in 1689 supporting Protestant William III and Mary II, a form of insurance that involved being on the winning side at a safe distance, his estate was destroyed by Montrose’s Catholic Jacobite troops. The damage was valued at £52,000, a sum sufficiently large to make Parliament reach for a creative solution rather than an open purse.

Accordingly, the Crown and Parliament compensated the Forbes family by granting them the perpetual privilege to distil grain into aqua vitae in lieu of paying excise duty. This arrangement appeared reasonable at the time, largely because no one involved had tried to imagine its consequences.

Serendipitously, four months before the privilege was granted, the Gaelic-Goidelic word ‘isque-bagh’ first appeared in Scotland. Language, like alcohol, has a habit of arriving just in time to legitimise what was already happening. Before long, Ferintosh and aquavity became the vernacular for Scotch itself.

This did not mean that whisky had suddenly been invented. Since the late fifteenth century, monastic stillories and household alembics had been distilling spirits for medicinal elixirs and victual preservation, the medicine being administered with optimism and the preservation largely theoretical. In July 1505, the Edinburgh guilds of Barbers and Surgeons and the Apothecaries were granted monopolistic patents to distil aqua vitae, thereby ensuring that intoxication was both professional and regulated.

By the early seventeenth century, small estates with single stills were distilling surplus produce into Scottish genever and flavoured spirits, such as Robert Haig at Throsk farm near Stirling. These were modest operations, tolerated because they were useful and ignored because they were small.

The Forbes privilege, however, was neither modest nor ignorable. Challenges arrived with regularity. In 1695, Parliament imposed a nominal annual fee of £22/4s/5d, which satisfied everyone who believed that symbols mattered more than arithmetic. In 1703, after a neighbour failed to annul Forbes’ advantage altogether, the court restricted his mashing of barley and oats to estate-grown grain, a ruling that was scrupulously observed in principle.

In March 1707, the Act of Union with England preserved the privilege, later adjusting the pro-rata in 1713 against the new malt duty and the lower yields of Scottish bere. This was fairness of a particularly British sort, carefully measured and quietly resented.

During the second Jacobite Rebellion in 1745, Culloden House and the Forbes lands were again pillaged, producing losses of £20,000 and a renewed sense that loyalty was expensive but potentially lucrative. The family expanded the estate from 1,800 arable acres in 1690 to 6,500 by the 1760s, while facing accusations of importing grain from neighbouring counties, which everyone agreed was outrageous and exactly what anyone else would have done.

Three additional distilleries were erected at Ryefield, Gallowhill, and Alcraig, and the original aquavity on Mulchaich farm at Bunchrew was upgraded in 1782. Commentators speculated that Ferintosh’s legal and cheaper whisky accounted for more than half of Scotch consumption, a statistic that explained both its popularity and the rising blood pressure of Lowland distillers.

Ferintosh’s peak year was 1784, when it distilled 268,503 spirit gallons on twenty-five 40-gallon pot stills, representing 36 per cent of all legal spirits in Scotland. In 1782 it began exporting to London, supplying spirit to petty distillers and rectifiers who obligingly turned it into gin and English brandy. From 1777, modern Lowland distilleries such as Stein’s Kilbagie and Kennetpans and Haig’s Cannonmills and Lochrin entered competition, while England’s twelve great capital malt distilleries produced millions of gallons for compounding markets. By 1785, Scottish exports to London reached 837,751 gallons, and resentment matured nicely.

The 1784 Wash Act, aided by persistent lobbying from the Lowland distillers, led to the Court of the Exchequer withdrawing the royal privilege in December 1785. The privilege was valued at more than £7,000 a year, but compensation amounted to the annual fee of £72/18s/11d. Duncan George Forbes received £21,850, which was sufficient to close the matter and insufficient to soften it. Without excise relief, production collapsed, ceasing in 1788.

With the ending of the Ferintosh privilege, “the whole population, abnormally swollen by the whisky monopoly … hundreds of men and women, thoroughly instructed in the art of distillation, emigrated with all their technical knowledge to other parts,” notably Campbeltown.

When Ferintosh lost its tax exemption, the whisky did not die. It escaped. It behaved like a highly trained criminal workforce, taking its skills to Campbeltown, the Lowlands, and anywhere the taxman was slow, distracted, or nursing a headache.

Robert Burns’ lament, “Thee Ferintosh! O’sadly lost!”, was therefore premature. Ferintosh was not lost. It was replicated. During the 1790s, dozens of small distilleries operated in the district, many selling Ferintosh whisky. In 1893, the Ben Wyvis Distillery adopted the name before closing in 1926.

Ghosts and imitators of Ferintosh continue to rock Scotland’s ancient isque cradle, because whisky, once set in motion by law, loophole, and accident, has never shown the slightest inclination to behave.