The spirit safe

Published October 3, 2021

Contents

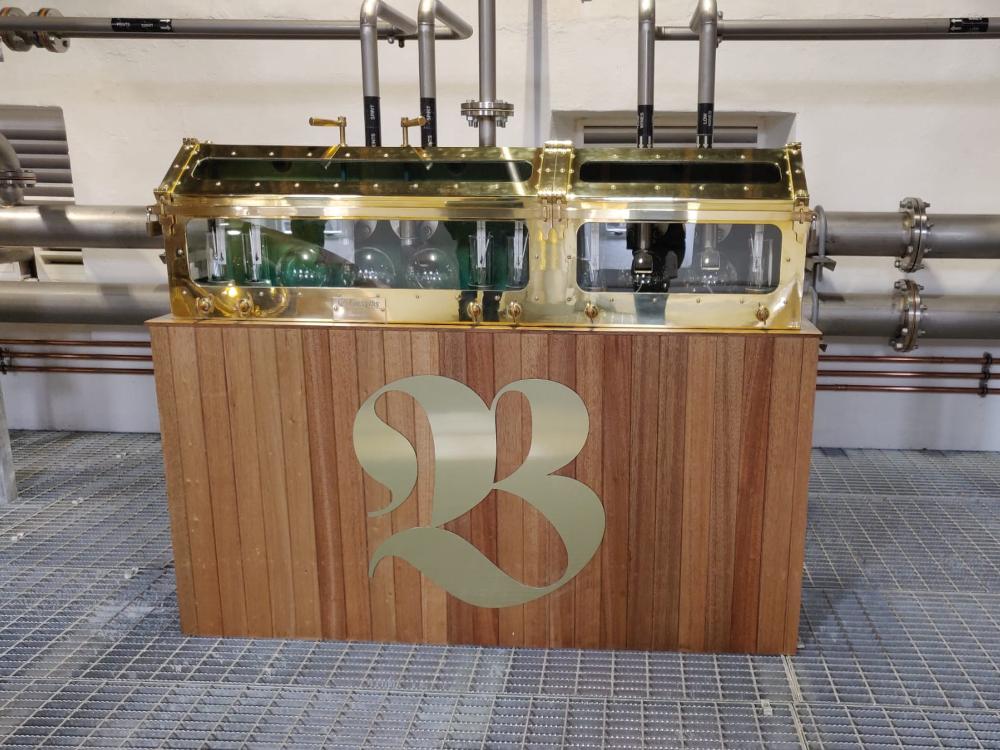

In almost every single Scottish whisky distillery there is a spirit safe through which every drop of new make flows. The spirit safe is an eye catching polished brass case with glass panes designed for two purposes:

- To allow the distillery to analyse and control the flow of the new make

- To keep track of the volumes of whisky made for tax purposes

Prior to 1983 only one key existed to release the padlock on the side of the safe, held by the local Customs and Excise officer. The excise man was tasked with measuring how much spirit was produced. Since 1983 the keys are now held by the distillery manager, and Customs and Excise ensure compliance by analysing and comparing expected alcohol production based on grain.

What is a spirit safe?

A spirit safe is a closed device that is used to control and track the distillation of Scotch whisky to ensure tax is paid.

The distilling of whisky in Scotland is not only subject to technical requirements but also to economic peculiarities. The spirit safe fits comfortably in to both categories. Used in virtually every distillery the spirit safe is the last station in whisky production before the freshly distilled new make is filled into wooden casks to mature into whisky.

Although the spirit safe and the production process have been completed, the master distiller has the option of checking the quality of the whisky during the distillation.

How does a spirit safe work?

After the distillation process in the pot stills, the fresh distillate runs into the spirit safe. Once there the liquid can be divided into three constituent parts by the stillman or Master Distiller. The new make is split into

- Foreshot (often called the head)

- Heart

- Feints (also called the Tail)

Of these three only the middle part ethanol, which makes up between 20 and 60% of the total distillate, is of sufficient quality that it is forwarded directly to the storage tanks to be filled from there. The other two parts are fed back into the distillation process joining the wash for the next round of distillation. This redistilation ensures that as little valuable alcohol as possible is lost.

The challenge of how to determine with sufficient accuracy when the foreshot is over and when the feints from the spirit stills begin to arrive is the role of the spirit safe. The measuring devices in a Spirit Safe provide the stillman with two values;

- The temperature of the distillate

- The density of the distillate measured by hydrometer From these values the stillman can determine the alcohol content of the liquid. If the alcohol level falls to 75% ABV or the incoming liquid no longer turns water cloudy, the distillate is diverted into the glass funnel and flows on to the spirit receiver.

Everything that has a higher ABV than 75% (the foreshots) are diverted into the second funnel onto the Low Wines & Feints Receiver. Later this funnel will be used again when the ABV reaches a point between 60%-70% ABV as determined by the cut*. These Feints are combined in the Receiver and will be added to the first round of distallation with the next batch of wort. The point of this is that all parts in a spirit safe can be operated from the outside using levers ensuring there is no physical contact with the distillate.

*The exact point of the cut will vary from distillery to distillery depending on the flavour profile desired. As the cut points will determine what combination of methanol, ester, aldehyde and fusel oil are kept, the master distiller carefully sets the cut points and thus decides on the character of the New Make, which later becomes the whisky.

With a thermometer and a hydrometer (hydrometer) the master distiller can determine the temperature and density of the New Makes. This enables him to recognize which part of the distillate is currently flowing through the Spirit Safe and act accordingly. The foreshots typically flow out of the still with around 75% alcohol. At 72 to 71%, the so-called middle cut is often made - now comes the valuable heart of the whisky. It flows until the final cut is made at 65 to 62% alcohol, after which the fusel oils arrive.

How long have spirit safes been in use in Scottish distilleries?

Many Scottish whisky distilleries can be traced back to more or less illegal distilleries that did not yet have a spirit safe in the still house. That changed with the Excise Act of 1823, which made legal distilling more attractive and illegal distilling more dangerous at the same time. The Excise Act is also one of the reasons why so many distilleries have their official founding date around 1823.

Examples of early distilleries

- Auchentoshan and Glenlivet (1823)

- Cardhu and Macallan (1824)

- Edradour and Glenkinchie (1825)

- Aberlour and Glendronach (1826)

Since then, anyone who wanted to legally distill whisky has had to install a spirit safe in the Still House and pay the alcohol tax to the British state immediately after the distillation. In order to be able to reliably understand the amount of distillate and to prevent the trade of duty unpaid whisky, the regulation was issued that the distillation process must be carried out in a closed system.

The invention of the spirits safe

The spirit safe was originally invented in 1819 as an ingenious invention for fractionating distillate. The peep-box which he called and patented “Fox’s Distiller’s Economist” allowed distillate to be checked through two panes of glass, at the front on the viewing side and at the back of the copper box, without it coming into contact without excessive exposure to air and evaporation. From this simple invention the spirit safe was quickly developed. The first was fitted and used for the first time in the Port Ellen distillery on Islay. Over time, engineers improved Fox’s peep-box into a hinged brass-glass box, which enabled pre-run and post-run checks and fractioning to be completed. The invention of James Fox thus became a kind of litmus test to check the purity of the distillate.

Little did James Fox know that just four years later his technical innovation would be used by the state as a weapon against illicit distilling. With the Excise Act 1823 legal distilling was licensed and certified if the distillery paid a fee of ten pounds plus a duty for each gallon of pure alcohol. In order to bring the concession from paper to practice, the watchful eye of the authorities had to control the distillation effectively This was achieved at the place where the new make flowed - on the opening control window of the spirit safe.

The authorities had free access blocked by attaching a padlock to the opening flap, the key of which was carried by a customs officer on his belt. This official oversaw the entire distillation process and, as the state authority, exercised sole control over the distillation. This simple measure of monitoring could only be practiced as long as there were only a few distilleries with a distilling license, which lasted until 1870. When the whisky boom started from that date, there was suddenly a shortage of staff, so the safe was sealed with an official customs seal. According to these regulations, the stillman was also assigned to the accountant, who had to handwrite all distillation in a large notebook with the date, alcohol content and information in gallons. From then on, the firing protocol served as the basis for collecting the distillation fee.

With increasing digitalization, the spirit safe disappears from the Scottish distilleries or survives as a functionless art object. Modern distilling is controlled either by the push of a button or entirely digitised, as at all large distilleries such as Roseisle, Glenlivet and Glenfiddich.